Modification to Aquaculture Lease Jervis Bay

This submission argues that there is no need for Council to take action in relation to private access paths to Callala Beach. At our property and those around us, there is no evidence that these paths are undermining dune stability or making erosion at times of storms worse in any way.

If the Council’s engagement with the community results in additional measures we can take to provide greater stability then we welcome that, but seeking to deny private access to owners of beachfront property is unwarranted and should not proceed.

Experience of dunes being cut by storm/erosion

We have owned a beach front home on Quay Road since early 1997. During that time we have experienced several events in which storms have caused some cutting away of the dunes in front of our property, and all along Callala Beach. As a result, you can be assured that we are totally committed to ensuring that the dunes remain as stable as possible and we have encouraged vegetation to grow in front of our home to support this.

Our lived experience is that the dunes are actually very stable. The first storm incident occurred only a few weeks after we moved in, in May 1997. At the time it was somewhat distressing to come from Sydney to find that there was a drop down to the beach which we recall being about 1.5 metres. However, within a few months the sand had washed back and we had once again an easy access onto the beach.

This has been the case in all other episodes over the years. It is happening again now as the 1.5 metre drop that resulted from the erosion earlier this year is now down to about 0.6 metre.

The following sequence of photos from July 2020 to January 2021 helps to demonstrate this:

|

In July 2020 there was an erosion episode as shown in this photo. This one wasn’t as severe as some others, but is still noticeable. |

|

By October 2020 much of the cut had been restored, as shown in this photo. This picture demonstrates clearly the way sand is pushed back and builds up the edge of the dunes once more. |

|

By January 2021, the cut is no longer evident as the dunes have been restored. |

An additional observation that we believe is relevant is that every incident of storm erosion that we have witnessed over the last 25 years has cut the beach to the same spot. That spot can be seen in this aerial photo taken in April 2010 showing where the vegetation and dunes have always ended. It’s at the ‘thinning out’ point highlighted in yellow that the erosion happens. Every time.

For example, compare the photo for July 2020 above with the following photo from the recent episode (August 2021):

The sand face here is in the same location as all other episodes have been. From our yard there is a 2 metre dip into a ‘valley’ which is heavily vegetated with saltbush and other plants, then a small rise to the beachside dune which is largely vegetated by tufty grass and runners. It’s at the point where the grass thins out that the erosion always takes place.

It seems therefore, that the dunes have an existing behaviour pattern that doesn’t need any further management. What happens now is a natural phenomenon that we must and do just live with.

Observations about impact of private pathways accessing the beach

To get to the main issue under discussion at present, the other thing to see from these photos is that there is no evidence at all that where our pathway meets the beach has created any additional erosion when a storm hits. In the photo above from August 2021, which is head on from the beach, you can’t see where our path is. The erosion cut is a clean line at the edge of the dune. (For information, our pathway comes to a point near the right hand edge of this photo.)

This is even more evident in the following photo, taken in April this year, which is directly head on to our pathway. The erosion is a clean line along the dune with no sign of the pathway causing additional erosion:

The following photo provides a perspective on our beach access path from the property side of things.

|

As you can see, our path is quite narrow in the midst of a lot of vegetation. We drop from our lawn into a ‘valley’ and then up the main dune before going down onto the beach. I believe that the dune closest to the beach has beneath it the sandbags that were put in place when the 1974 severe storm incident took place. |

Conclusion

One final observation in relation to pathways is that the erosion events typically impact all along the length of Callala Beach, not just in front of the houses. This certainly was the case with the east coast low episode earlier in 2022. The same erosion cut could be seen all the way along the beach towards Huskisson where there are no private pathways. That surely demonstrates that the small, narrow paths from the houses along the beach create no greater impact on the dunes.

It would be distressing in the extreme if our access to the beach was to be restricted because of an unnecessary policy. Doing so would have no impact on dune stability, which is in any case quite satisfactory already.

We urge Council not to take such action.

The most recent in a sequence of dreaded East Coast Lows to affect the NSW coastline during the first half of 2022 has teased out some interesting observations.

This early autumn storm moved slowly southwards from Queensland before heading off towards NZ, leaving a trail of havoc and damage to public infrastructure along open coastal beaches as amply reported in various popular media.

Callala Beach was of course exposed to the same weather system and sustained typical erosion from a storm of this magnitude and direction, including a bite of about 1 metre into the primary dune face and substantial movement of beach sand to where it is now presently situated directly off the beach.

Let’s compare these two situations:

- The reported damage to open coast beaches was principally to seawalls and promenades, that is man-made interventions built to resist the power of a rampant ocean and so protect the coastal interface. It is pretty clear from the attached photographs as to which won that battle. The sand is likely to have moved well away from these beaches, through being subjected to strong lateral forces that can move it to other places up or down the coast in such events. The broken infrastructure must be repaired or replaced, as it will need to be again in future events.

Exposed infrastructure at Queenscliff and Collaroy April 2022.

Unlikely to repair itself with absence of vegetated foredune (Source: SMH)

- The damage to Callala Beach, some 10km inside Jervis Bay was very different to this. We are blessed with a precious, natural coastal dune system that remains intact: the sand is now sitting just off the beach waiting to be gradually pushed back up by tides and wind. This system will steward the natural, capital-expenditure-free repair of the beach front over coming months.

Movement of the primary dune position over time is dynamic as a result of these forces. As discussed in a previous blog, Callala Beach has been a building beach due to its location inside Jervis Bay. Thankfully catastrophic dune damage such as occurred in the 1974 storms is very rare, however the natural beach repair process at Callala has claimed back 30 metres of the Bay since then.

Callala Beach foreshore after East Coast Low of April 2022.

Foreshore damage is minimal where dune planting is dense and rapidly healing.

This is essential context for anyone interested in coastal processes, and should be fundamental to any planning body that has agency over coastal management. Unfortunately, Shoalhaven Council seems intent on planning the foreshores of the entire LGA coastline with a broad brush of dumbed down uniformity, if their proposed amendments to the LEP and DCP are anything to go by. The Department of Planning is a powerful but largely anonymous by-stander, apparently preferring simplistic, one-size-fits-all desktop-driven outcomes over a more tailored, real-world approach that would embrace the tremendous beauty and diversity of the forces that shape our coastline, rather than deny them.

Callala Beach foreshore after East Coast Low of April 2022.

Foreshore damage is much greater at public accessways where there is a lack of dune planting to provide coverage.

The past is of course no guarantee of the future (if in doubt ask a financial planner). What needs to be pursued is research into ideas about how rising sea levels can be mitigated to ensure that Callala Beach remains the exceptional place that it is. Rising future sea levels mean that each storm starts from a higher baseline, and in combination with king tides and storm surge the future is indeed unknown territory. The CFA can play a significant role here, as an advocate for sustainable, necessary change.

Money can solve a raft of problems, but it is not likely residents or Council will be in a position to accept or fund exposed breakwater rock walls such as along the Botany Bay foreshore, or the massive revetment-style concrete ramparts recently constructed at Collaroy.

Fortunately we have a more predictable and natural environment in Jervis Bay that we need to work with to ensure a superior, more sustainable long-term outcome.

The Shoalhaven is blessed with a magnificent coastline of headlands, beaches, bays, basins, creeks, rivers and lakes, set in a unique natural landscape that in many ways defines the essence of what the NSW South Coast is. Global warming has many consequences with one - sea level rise – being a key issue that should be at the fore of the CFA’s mission.

Unless arrested by a de-carbonised world, sea level rise will re-shape land/water interfaces across the globe, including our little 5.6km stretch of sand inside Jervis Bay. The threat is real over time, and the CFA is committed to understanding and mitigating its impacts.

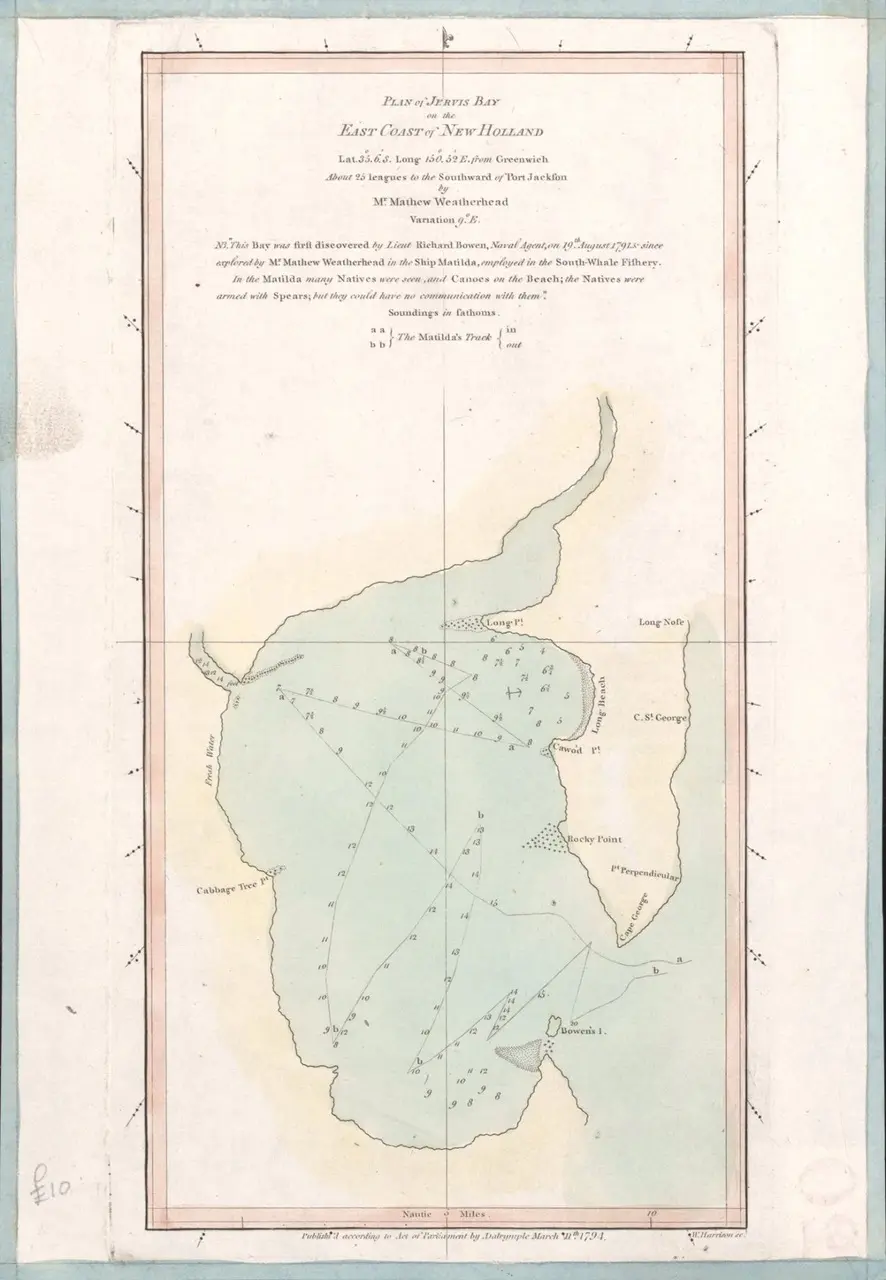

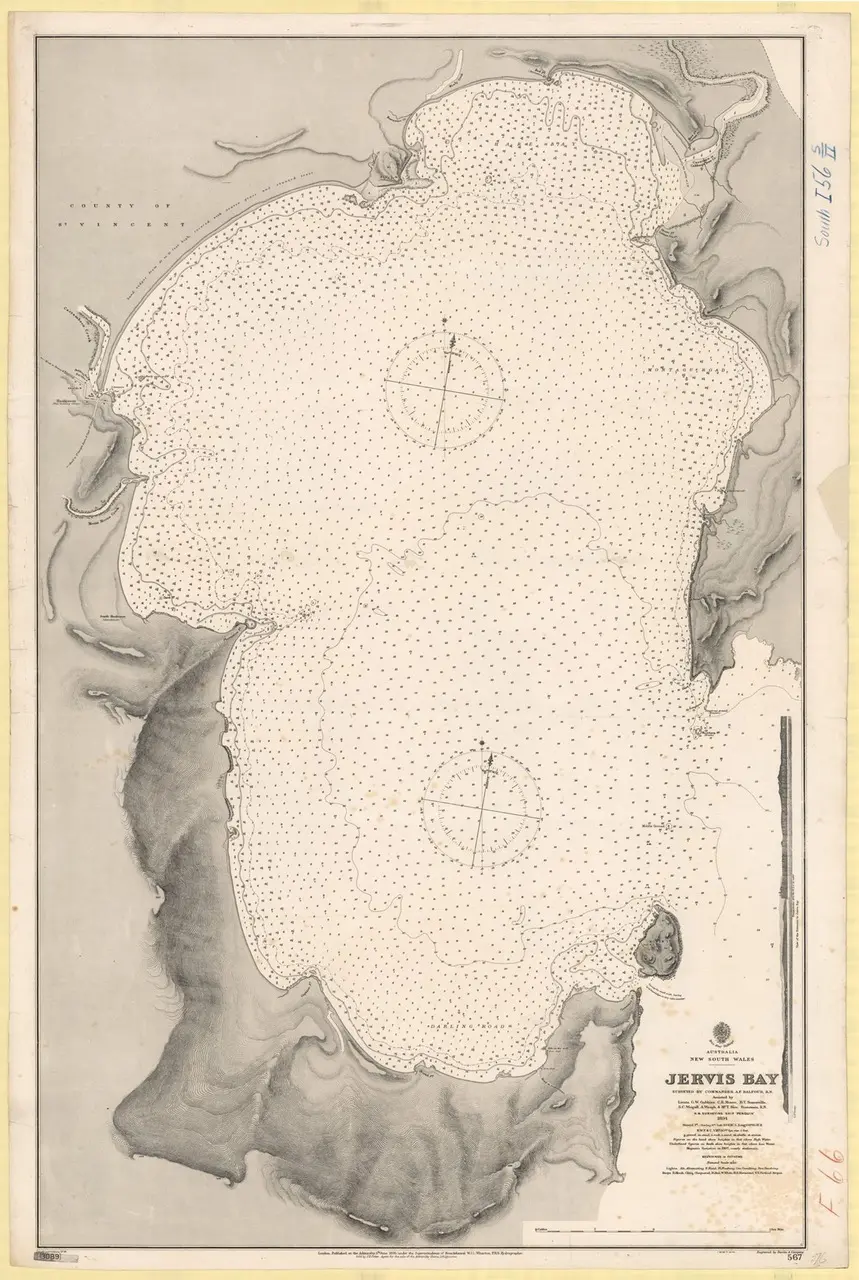

1796 Map Jervis Bay

What needs to be better understood by stakeholders – residents, Council, NSW Govt agencies - is that each place has unique circumstances that directly affect how sea level rise will impact upon it. For example, an open coastal beach is exposed to littoral (sideways) currents and drift that can transport huge volumes of sand along the coastline and sometimes in large storms, even around a headland where it becomes trapped in the next embayment – a recent example is loss of the beach sand at Byron Bay. A beach contained within a bay – such as Callala – is not exposed to the same forces however. When Callala Beach is subjected to large south-east swells the sand is sucked out off the beach and sits directly offshore until coastal processes (tides and wind) slowly but surely push it back onto the beachfront. Long term residents are entirely familiar with this natural rhythm and process.

Another interesting fact is that prior to subdivision and construction of the settlement, aerial survey photography clearly maps the village being built over what were dozens of perfectly parallel, concentric heath-covered dunes representing the inexorable, eastward movement of shoreline position over previous millennia. In other words, this indicates that historically the shoreline has advanced into the Bay, and not vice-versa. If more evidence is needed consider the relatively recent twin storm events of May 1974, considered by meteorologists afterwards to be a 1:1000 year occurrence. The very substantial dune bite line from these storms remains visible today, approximately 30 metres inland of the current primary dune face.

1894 map of Jervis Bay

This means that Callala Beach has historically been a “building beach”, not a receding beach. Why? Simply put, because our fine white sand is trapped in Jervis Bay, and like our dolphin community (another story), a very long-term resident with no foreseeable impetus or known plans of going anywhere!

So while sea-level rise will impact on Callala Beach, it is quite simply wrong to assume that its effects will be the same as elsewhere in the Shoalhaven.

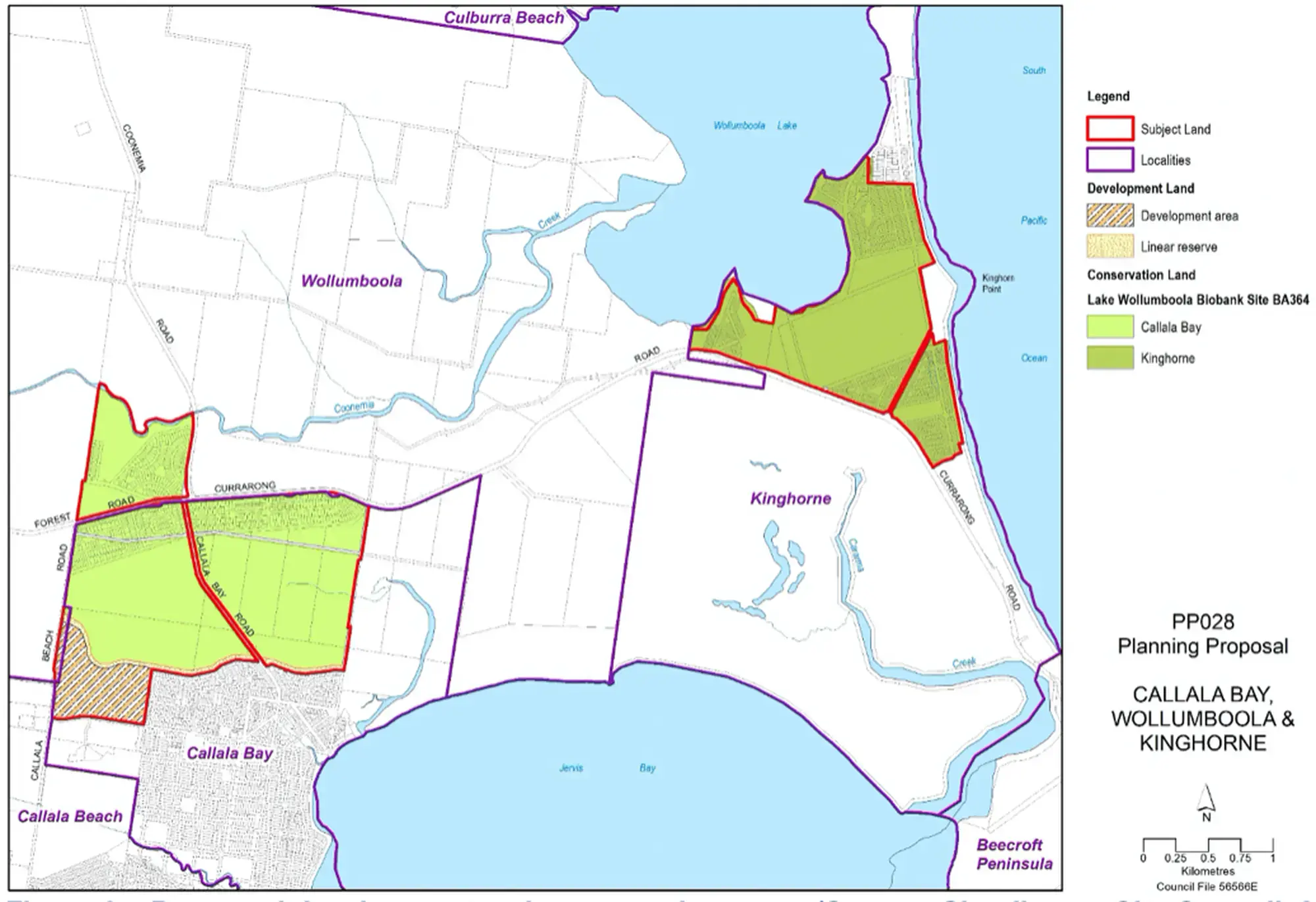

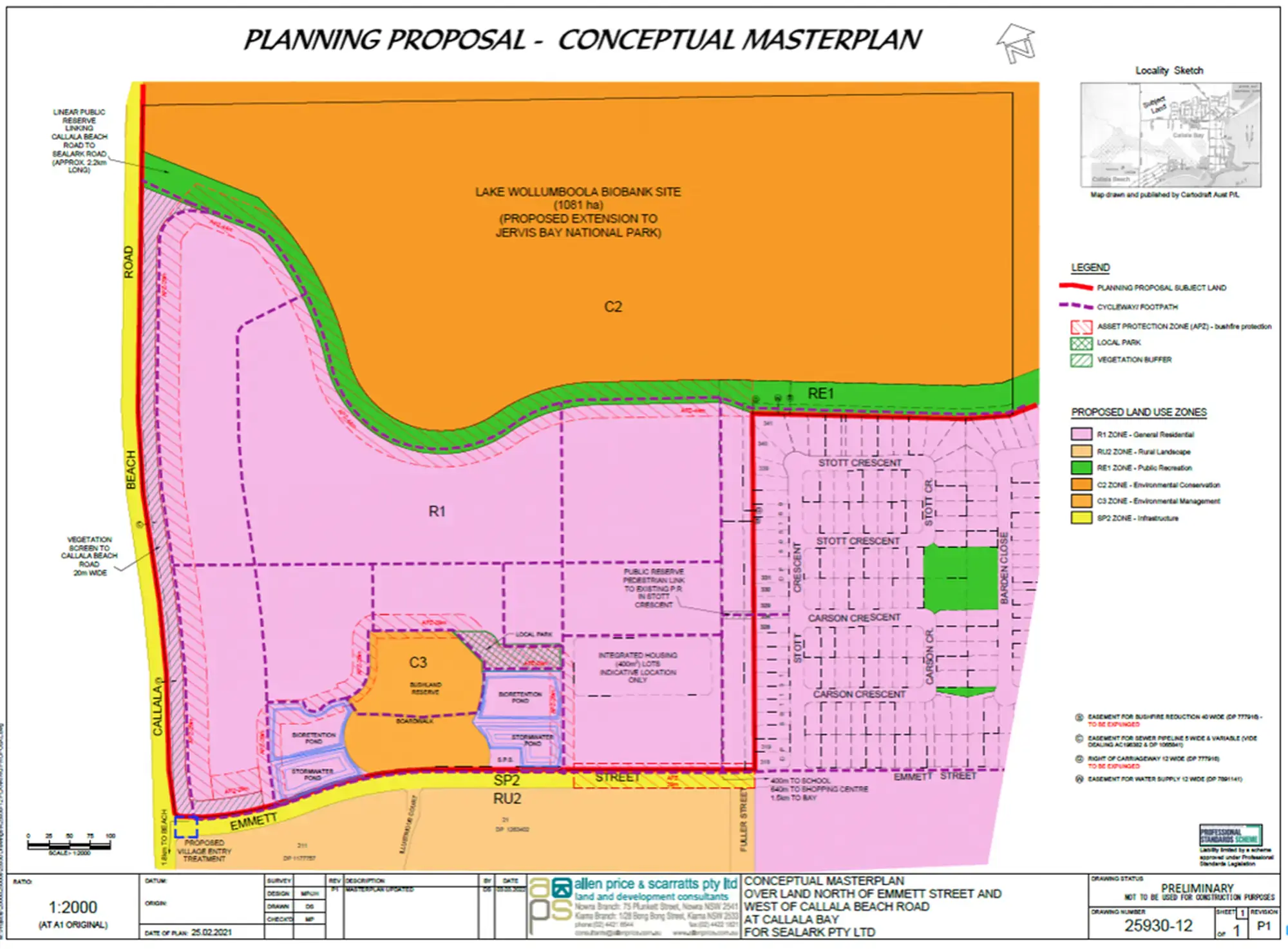

Which brings us to the point of this discussion. Council’s recent public exhibition of PP026 – Coastal Hazards Review (Revised Approach) was prepared at the behest of the Dept of Planning. In a nutshell, it seeks to replace a reasonable working document (DCP 2014) with one that now designates entire swathes of coastal property up and down the coast as 100% subject to “beach erosion hazard”.

As background Council prepared a set of coastal hazard lines based on then current science over a decade ago, to ensure that new coastal development would be reasonably protected from global warming impacts. The lines were based on projected data for 2025, 2050 and 2100. More recently (2016) Council established an on-line mapping system linked to the DCP, that allowed it to adjust the location of these lines to reflect emerging/dynamic data and so avoid the problems of fixed lines in conventional planning control documents becoming progressively obsolete. All good so far! The Dept of Planning were not happy with Councils most recent approach to an updated DCP however, and sought to have it amended to be consistent with their view of good planning methodology.

The resultant rationale in the new proposal for designation of affected property across the entire Shoalhaven coastline distills down to simply this – if any part of an individual land holding is traversed by a section of a coastal hazard line, then the entire property is colour-coded bright orange and designated as “Beach Erosion Hazard”. At its most extreme, PP026 proposes that the entirety of Navy land ownership at Beecroft Peninsula is classified as “Beach Erosion Hazard”, presumably because a hazard line traverses this massive single land holding at a location inside Jervis Bay. This is nonsensical, inaccurate and highly prejudicial to property owners. It is also a great leap backwards from the existing DCP mapping, which at least identifies the area of each property where the coastal hazard zone is located, not the entire property!

Together with the building beach scenario described above, this same argument can be applied for beachfront property at Callala Beach. Council is attempting to apply a “one size fits all” approach to mapping across an extremely diverse region, but good planning process simply does not work that way. However what it has managed to achieve already is a strong negative impact on the perception of property values on Quay Rd.

Many residents have written to Council expressing their concern with this poorly conceived proposal. The CFA needs to prompt Council to explain the rationale and detail as it applies to Callala Beach: it is simply unreasonable to expect that residents should accept on face value this simplistic, “one size fits all” approach to thoughtful planning of the unique Shoalhaven coastline.